Dakinis in the Life of Garab Dorje

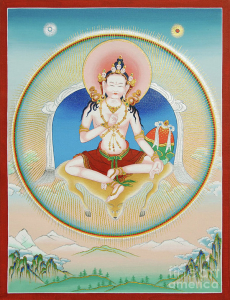

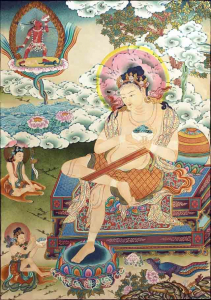

Garab Dorje – The First Human Teacher of Dzogchen, painting by the extraordinarily talented Sergey Noskov.

Garab Dorje is considered the first human teacher of the Great Perfection (Dzogchen). The legend of his life is fascinating on several counts. One feature I have always found puzzling is why he meditated for thirty two years in the realm of the Hungry Ghosts. In Tibetan Buddhism, the realm of the Hungry Ghosts is a world full of insatiable hunger, thirst, obsession and suffering. It is considered one of the lower realms. It could have been any one of the realms, so why that one in particular? In a version of the past life of the Buddha, he first gave rise to bodhichitta in the hell realm. See my article that discusses this here – Pema Khandro’s Bodhisattva article. In any case, thirty two years alot of time spent in meditative stability anywhere, especially in the bad circumstances of the Hungry Ghost Realm, which only underscores how potent his meditative prowess was. But another fascinating thing about his life, is the role of the Dakini in his story.

A Dakini first appears in his life during when his mother, a nun, was meditating. She had a dream like vision of receiving a vase initiation and told her attendant about it. The attendant, who was named ‘Dakini,’ translated this dream to the nun. She told this nun that she would give birth to a nirmanakaya, a highly realized being. Later on after the nun did indeed have a child and she was terrified. Since she was a nun, she was afraid would people would think so she discarded the baby, leaving the baby in a pit of ashes. This is a really horrifying point in the story, but sadly, we can see themes of infanticide in many East Asian stories of this period. So she left the baby and ran away hoping no one would know. When she came back three days later, the baby was unharmed. She found that Dakini’s appeared in the sky making offerings to baby and thereby sustaining him.

This story is a useful example of the descriptions of Dakinis, because the first description before he was born is a human person, and the second one is more like an ethereal divine being appearing magically from the sky. This is how the Dakini is described in Tibetan Buddhism, it can be a term to describe highly realized human beings or it can be a term to describe divine or semi-divine beings and there are even ones that are monstrous as well. In Garab Dorje’s story, since offerings are being made to him by Dakinis as divine beings, this implies another sign that this was a realized being.

Dakinis appear in the story of Garab Dorje again when Garab Dorje put the teachings in writing. When it was time to write down 6,400,000 verses of esoteric Buddhist teachings, Dakinis appear again to help him. The Dakini of Immutable Space and the Dakini of Limitless Enlightened Qualities come to his aid as well as others. One Dakini is even placed in charge of holding the volumes of teachings, the Dakini Semdenma.

Later the first students to whom he teaches the Great Perfection (Dzogchen) to are – hundreds of thousands of Dakinis. Their mastery of the teachings is expressed in his legend by saying they all attained the rainbow body. The attainment of the rainbow body is how highly realized adepts are thought to die in the Great Perfection path. This also intimates that Garab Dorje’s first Dzogchen students were hundreds of thousands of human females, since the rainbow body is attained by human beings, not ethereal, divine or semi-divine dakinis, but human ones. However, we should be cautious in assuming that this literally infers the participation of actual females. This is a narrative, not a documentation of a literal history, but instead an aesthetic expression of a history of important Buddhist principles. Some Buddhists do take such stories literally of course, because Tibetan Buddhism is incredibly diverse in interpretation and practice. Diversity is beautiful. In any case, the presence of female students in such an important legend, even though it is not necessarily evidence of mass female participation, is a positive sign of the culture of the Great Perfection teachings. From its early era, the Great Perfection fostered a culture of relative inclusivity within non-celibate communities that did include female adepts.

So in the life of Garab Dorje – Dakinis prophesied his birth, took care of him when he was a stranded baby, helped in the recording of the teachings, help to preserve and protect the teachings, and Dakinis are the first students and first realizers of the teachings. We could even consider them ultimately as the first embodiments of the teaching (if rainbow body could be considered the ultimate form of embodiment in a context the body of light is considered the true body in Dzogchen).

About the Image

This image of Garab Dorje is a painting by Sergey Noskov. His are the most beautiful thangka paintings and it is possible to order prints. Among my favorites of his are the Ekajati and Longchenpa. See: https://fineartamerica.com/featured/garab-dorje-sergey-noskov.html?product=art-print

_______________________________

Author

Dakini Stories are written for the Dakini Mountain fundraiser by Pema Khandro. They are based on Tibetan Buddhist legends of Dakinis. Pema Khandro is a Buddhist teacher and scholar specializing in the traditions of Tibet’s Buddhist Yogis and their Great Perfection teachings. Learn more about Pema Khandro here: Pema Khandro Rinpoche

Sources

Khenpo, Nyoshul. Translator, Richard Barron. Marvelous Garland of Rare Gems: Biographies of Masters of Awareness in the Dzogchen Lineage. (Junction City: Padma Publishing, 2005). 37-38

Diversity Dakinis

Diversity is beautiful

Diversity is the norm

Appreciating diversity helps us live more wakefully

Diversity awareness helps us live more compassionately

Dakini Mountain is dedicated to celebrating diversity

Dakini Mountain is named after the Dakini principle because this term – Dakini – expresses the principle of diversity in creative expression that is the phenomenal world. The notion of Dakini in the Great Perfection (Dzogchen) goes hand in hand with the teachings of the five elements and the five wisdoms. Each of these are represented by a variety of enlightened female figures, known as Dakinis, the Five Wisdom Dakinis.་They are different colors, different body shapes and different personalities thought to represent the spectrum of wisdom qualities in human beings – joy, clarity, dignity, fearlessness and peace.

Dakini is the Sanskrit term and the Tibetan word is mkha’ ‘gro, which means traveling in the sky. It can also be rendered as traveling in space. One popular rendering is “sky-dancers.” The space and sky that the Dakini travels in – is the space of reality as it is.

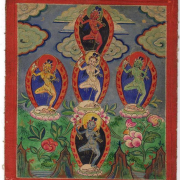

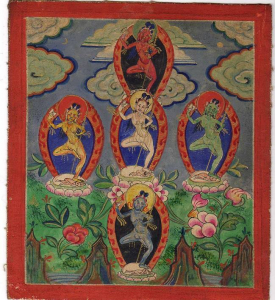

A mandala of the Five Wisdom Dakinis, with the unusual feature of the Red Dakini in the North, even though we most commonly see the white or blue one in the North. Another case where Tibetan Buddhism’s number one rule is – Diversity.

According to the Great Perfection (Dzogchen), every living thing communicates special qualities of this Dakini wisdom. It is communicated in qualities such as spaciousness and energy, or power and intimacy. Usually we think of such qualities as contradictory or oppositional. However, in nature we see contradictory qualities co-existing to express extraordinary beauty. The Lotus Dakini wisdom is present as the luscious beauty of nature. The Jewel Dakini wisdom is present as the overwhelming power of nature, its nobility and dignity. The Vajra Dakini wisdom is present as the clarity and decisiveness of nature, its intensity and intelligence. The Buddha Dakini is present as the spacious accommodating quality of the sky, its stability and openness. The Karma Dakini is present as the quality of change, of action, activity and accomplishment. In Buddhist meditation practices featuring the five wisdom dakinis, their mandala implies an opening to the diverse qualities of enlightened wisdom that drive the phenomenal world. Therefore, when we appreciate the sacred wisdom of the Dakini principle, we befriend our world and therefore we can be friend the basic ingredients of own minds.

Sometimes Buddhist discourse is used to perpetuate entrenched power structures by denying diversity. One major is example is using emptiness discourse to deny diversity discourse. For example – the idea that if one is a Buddhist one should not be a feminist, because gender is empty. However, this logic is faulty, because if all identities are empty and therefore useless in their emptiness, then one one not need to even identify as a Buddhist. On the contrary, identifying as a Buddhist is useful. According to Mahayana thinking, identities fall into the category of conventional truths, functional, but contingent truths that have useful effects when they are used. This notion of emptiness is talked about in divergent ways according to differing schools of Buddhist philosophy. (Truly, the number one rule of Tibetan Buddhism is diversity). In the Great Perfection (Dzogchen) emptiness is posited in a positive way – it is said that emptiness is always co-emergent with presence. Or it may also be stated by saying that emptiness is co-emergent with appearances. In other words, all dynamic, diverse appearances are the creative interplay of emptiness and presence. This way of framing emptiness doesn’t negate the world as we know it, nor does this emptiness philosophy negate our identities and social world. Instead it highlights how our identities and social world emerge as both empty and present. This concept is reiterated in the notion of the Five Wisdom Dakinis in their principle as the empty and present quality of mind, emotions and the natural environment.

Today, Buddhism is practiced and taught in contexts that are extraordinarily diverse. This diversity is reflected in race, ethnicity, cultural norms, experience, age, language, socioeconomic status, family dynamic, health, physical abilities, educational background, religious background, sexual orientation, gender and physical appearance. This diversity will contribute to the teaching and transmission of Buddhism and its future in positive ways. Dakini Mountain is named after the Dakini principle as a celebration of diversity. Dakini Mountain will be a spiritual center dedicated to building bridges and celebrating diversity from its origins in the five elements and the five dakinis, to its expression in a post-modern, dynamic community working together to meet the demands of serving, studying, practicing and training in a new diversity sensitive era.

Author

Dakini Stories are written for the Dakini Mountain fundraiser by Pema Khandro. They are based on Tibetan Buddhist legends of Dakinis. Pema Khandro is a Buddhist teacher and scholar specializing in the traditions of Tibet’s Buddhist Yogis and their Great Perfection teachings. Learn more about Pema Khandro here: Pema Khandro Rinpoche

Image

This image came from a 19th century five Dakinis image at this museum: https://museum.oglethorpe.edu/category/exhibits/portals-to-shangri-la-masterpieces-from-buddhist-mongolia/

A Dakini Messenger

Dakinis in the Life of Naropa

by Pema Khandro

Dakini of the Words & Meanings

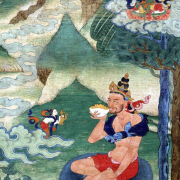

Whenever people tell me what they think “Dakini” means, I remember the scene in the Naropa story. It starts with this foreboding phrase, “A shadow fell over Naropa…” But then it goes onto tell a story of the Dakini as a quirky messenger for the importance of meditation practice. Here is the story in short.

A shawdow fell over Naropa… Naropa turned and saw an old woman with bizarre features. Naropa was a great scholar and triumphant debater at Nalanda. This was the famous Buddhist University in Naropa’s lifetime, the eleventh century. Naropa was a famed Buddhist intellectual there. One day, Naropa was studying when a shadow fell over him. He turned and that was when he saw this woman with disheveled hair, a wrinkled face, a dark blue complexion and a walking stick. She had a twisted nose, long ears and a hump-back. She ask him what he was studying and he told her “I am studying grammar, epistemology, vows and logic.”

She said, “Do you understand the words or the meaning?”

Naropa said, “I understand the words.”

Hearing this, the old woman began laughing, dancing, and waving her stick in the air.

Then Naropa added, “I also understand the meaning.”

Hearing this, the old woman began to weep and shake. She threw her stick down.

Naropa was confused and asked her why she was so upset now and why she had been so happy before. She said, “I was happy because at first you did not lie when you said you understood the words. I was sad when you lied and said you understood the meaning.”

Naropa immediately knew that what she said was true. Despite being renowned as a scholar, he only  knew the concepts and not the meaning. It had remained purely theoretical. He had not integrated what he had studied and he had not had deep insights into the meaning. So he asked her, “Who understands the meaning then?” At that point the old woman told Naropa about her brother, Tilopa, and this was the beginning of his search for his teacher. After their exchange, the woman, being a Dakini, then vanished, like a rainbow in the sky.

knew the concepts and not the meaning. It had remained purely theoretical. He had not integrated what he had studied and he had not had deep insights into the meaning. So he asked her, “Who understands the meaning then?” At that point the old woman told Naropa about her brother, Tilopa, and this was the beginning of his search for his teacher. After their exchange, the woman, being a Dakini, then vanished, like a rainbow in the sky.

The legend of Naropa and the Dakini is one that communicates the tension between intellectual practice and contemplative practice, between monastic institutions and adepts living outside the monastery. Buddhism has a rich intellectual history, a prized resource of the tradition. And yet at times, we can witness the warnings in Tibetan literature against developing intellect at the cost of knowing the meaning of the tradition through meditation practice. Ultimately, both study and practice could be regarded as equally essential to the path. Stories like this express moments of recognizing the problem of going to one extreme without attending to the other facets of learning – namely, experiential learning.

Dakini as the Nature of Mind

The Dakini principle is featured another time in Naropa’s life story.

This is during one of Naropa’s trials when his teacher tells Naropa, “Look into the mirror of your mind, the radiant light. The mysterious home of the Dakini.”

Here the Dakini is used as the term to name the indwelling luminosity that is the ground of innate presence in all beings. This indwelling nature is not something created by study or practice. In Tibetan Buddhist esoteric traditions such as Dzogchen, this innate luminosity is a fact of being – uncontrived, and unconstructed. Therefore, study and practice are ways to connect with what is already innate and authentic. Buddhist meditations are methods of letting go of all the neurotic embellishments that overwhelm one’s attention. When these embellishments become reified they become the basis of confusion and suffering.

It’s worth noting here that Naropa’s journey towards awakening is a story of undergoing extreme hardship, testing, trails and even abuse for the sake of pursuing spiritual awakening. He goes through grueling trials to overcome his privilege, entitlement, arrogance, and prudishness. Other trials seem to be trials of endurance proving his diligence. (1)

In Naropa’s life – we can see the Dakini principle functioning in two ways – to shock Naropa out of his privilege and awaken him to his neglect of practice, and secondly as a reminder that he has luminous wisdom within him.

Footnotes

(1) Here I am highlighting the Dakini encounter from Naropa’s story. However there is much more to his story, some of which is shocking and outrageous and yet it is considered a kind of coded story that alludes to truths of the spiritual journey. It’s important to remember such stories like those of Naropa’s outlandish acts of sacrifice in training should not be taken literally. They are true in a different kind of way than literal truths, they are offering symbolic truths that use hyperbole to provoke deep questions and open up possibilities for understanding human life in a Buddhist framework. One of the most provocative questions of Naropa’s life is how far is one willing to go for spiritual awakening? Despite some readings of his life story, if we take the Great Perfection teachings seriously, then it is unnecessary to jump off cliffs or suffer physically or endure abuse because we all have buddha-nature and it can be found in us as we are. However, a reality we all face is sacrifice and hardship for the sake of growth and perhaps that is what Naropa’s trials are all about. I see Buddhist narratives like Naropa’s as artistic and provocative literary presentations of Buddhist philosophy, practice, culture, and identity – not as literal stories to be followed – more as outlines of Buddhist principles and questions. In this sense, Naropa’s story could be seen in so many different ways, that is the point of Buddhist stories, they demand interpretation.

Author

Dakini Stories are written for the Dakini Mountain fundraiser by Pema Khandro. They are based on Tibetan Buddhist legends of Dakinis. Pema Khandro is a Buddhist teacher and scholar specializing in the traditions of Tibet’s Buddhist Yogis and their Great Perfection teachings. Learn more about Pema Khandro here: Pema Khandro Rinpoche

Sources

Dowman, Keith. Masters of Mahamudra; Songs and Histories of the Eight-Four Buddhist Siddhas. (Suny Press: New York, 1986).

Guenther, Herbert. The Life and Teaching of Naropa. (Oxford University Press: New York, 1963). 24-30

Help us Bring Dakini Mountain to Life – Learn about our Fundraiser and Plans Here